In explaining her work. Raffaela Mariniello wants to stress this type of problem, closely liked in particular to the type of research she conducts. "In cities such as Paris, Rome or Milan - she says - it is impossible to imagine the difficulties that arise when taking photographs in Naples, especially for a woman".

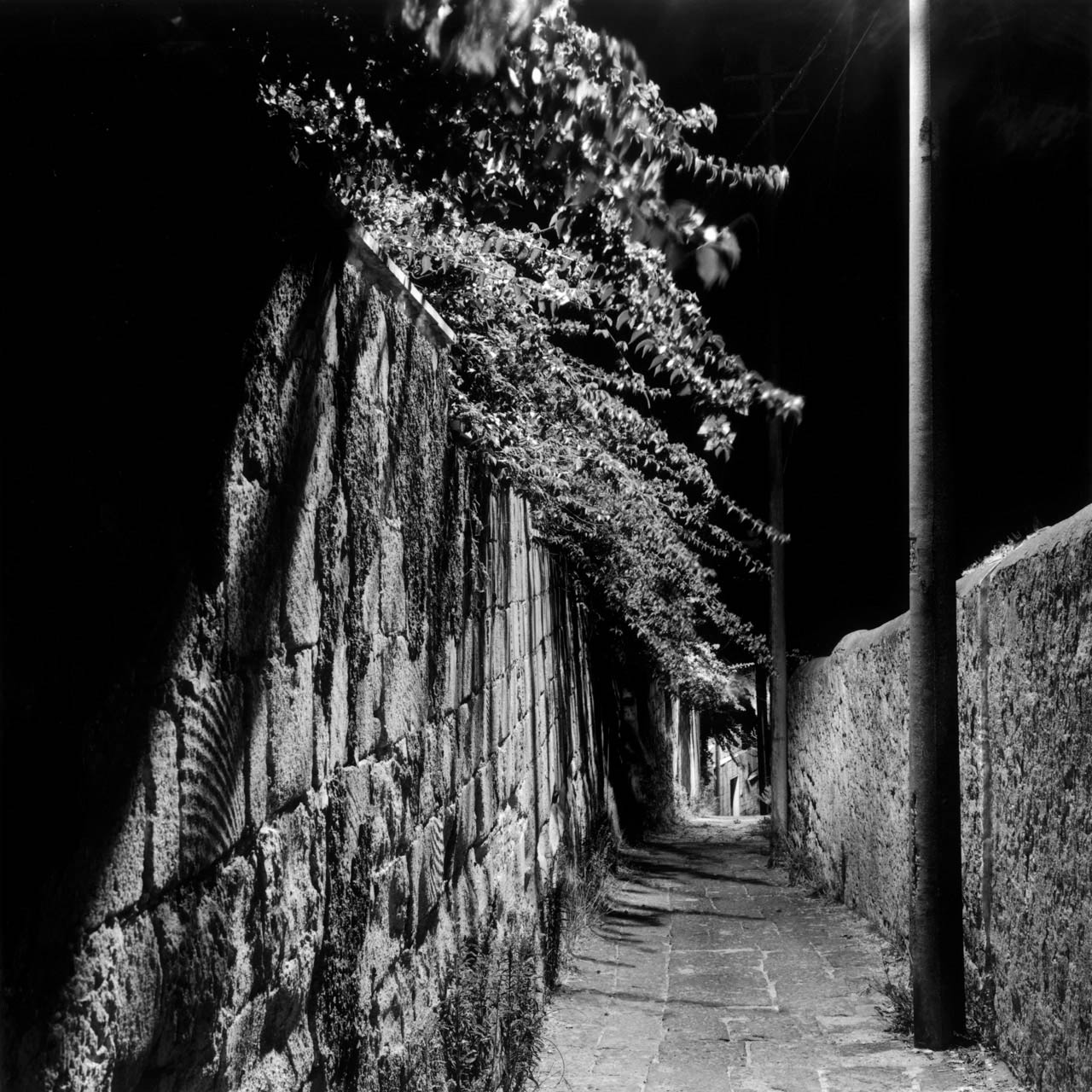

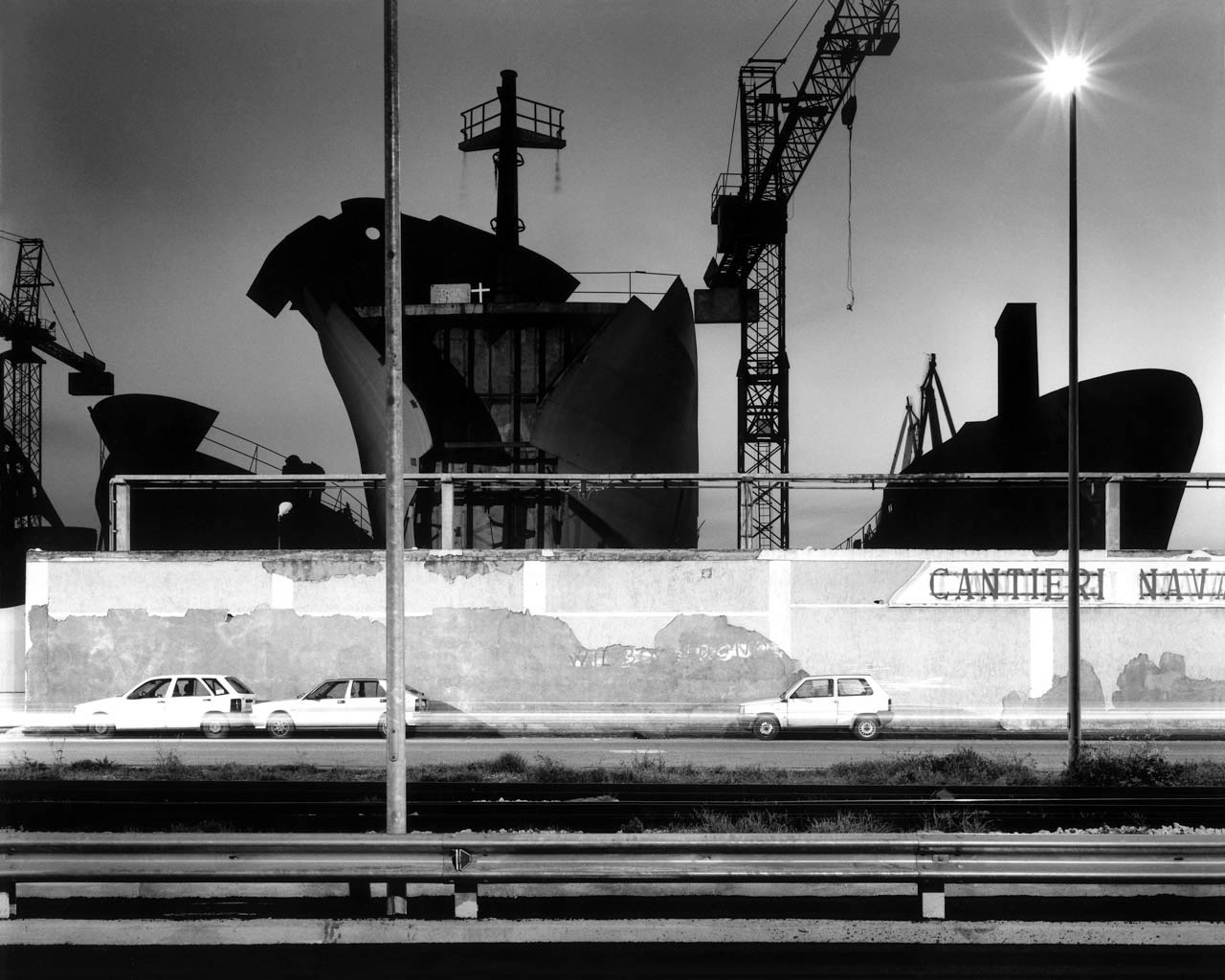

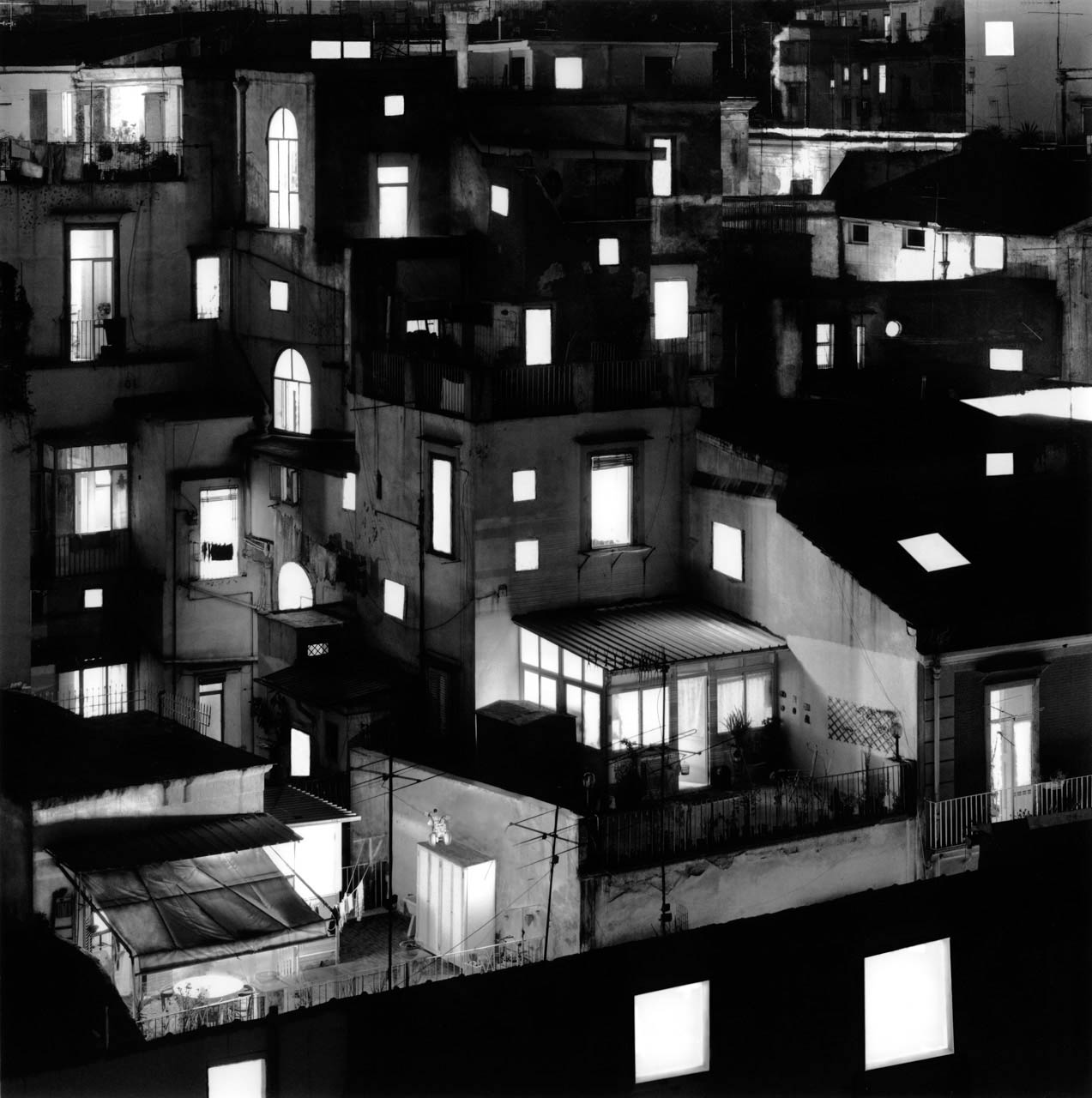

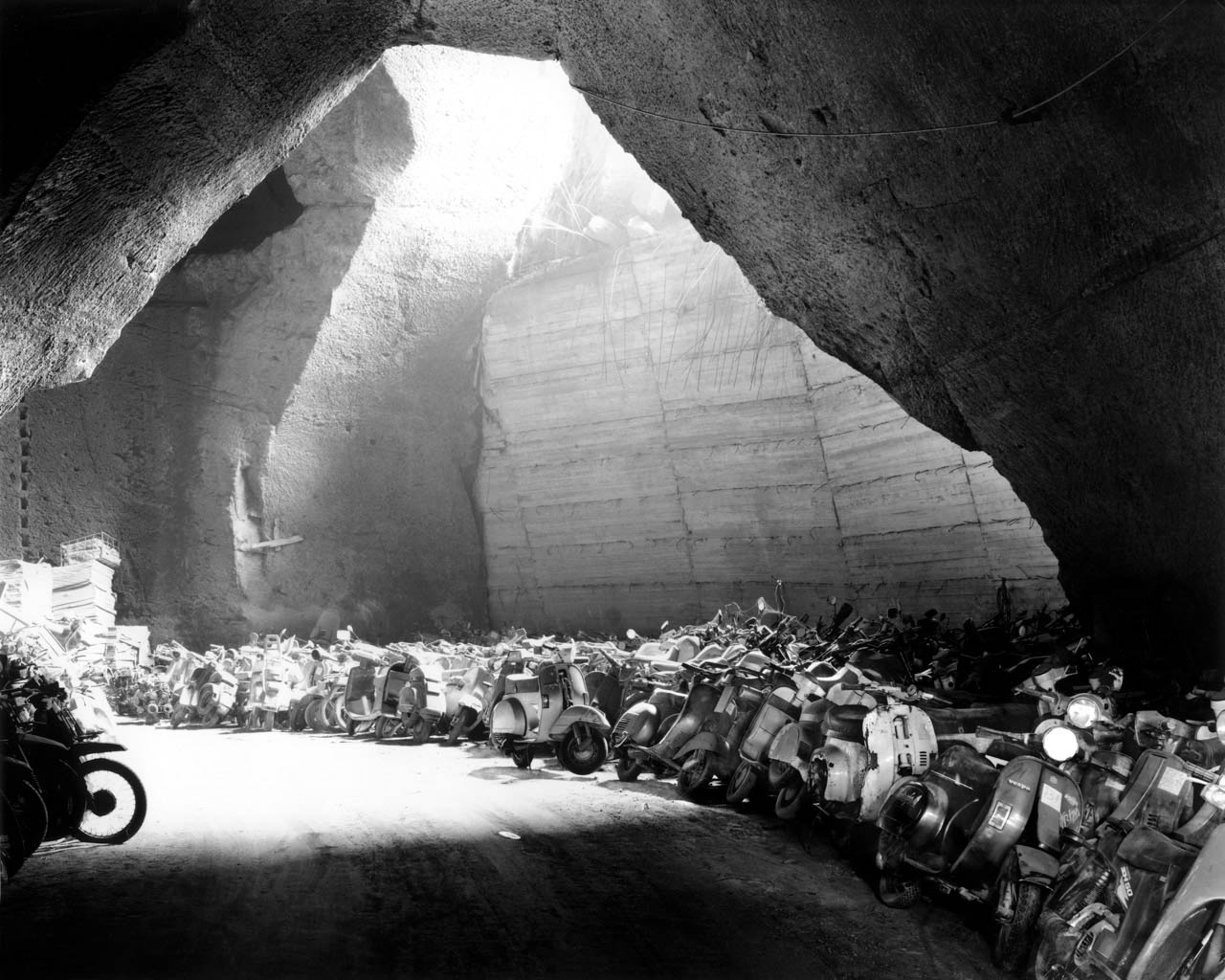

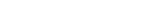

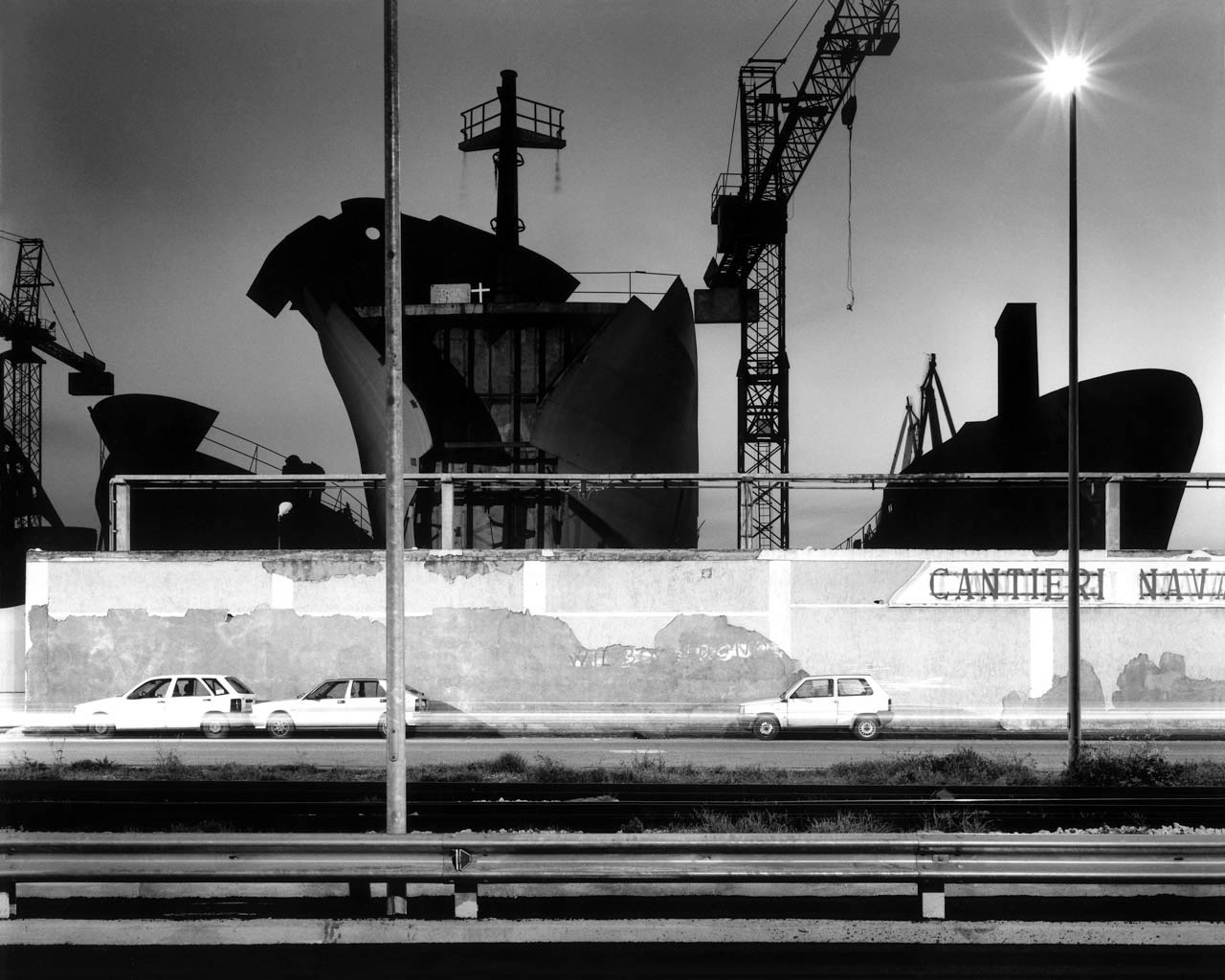

Dusk. Raffaela Mariniello, as we were saying, loves this time of the day because it enables her to mix natural and artificial light. With an approach comparable to that of Caravaggio, she believes that because intense diffused light illuminates everything without differentiation it ends up hiding things. So when that time of the day comes, she sets her 9x12 on the tripod and starts hitting the things she wants to highlight with her flash. This is how her pictures are born, with long exposure times ranging from ten seconds to fifteen minutes. The sea takes on the appearance of a plank and the sky becomes a trail of smoke. Equally, objects that do not remain immobile create a pleasantly blurred effect.

In this search, however, the photographer does not just use the flash as a means to highlight certain things, it is also a weapon with which she hides others.

This is the case of messages on advertising posters - when struck repeatedly by the flashlight they eventually disappear.

In this way, Raffaela Mariniello gives the terrifying intrusion of advertising its just deserts, practising a salutary visual ecology.

She does not only take away. Occasionally she adds. “Sometimes - she says - I see a background I would like to photograph, but it doesn't have objects that I want in the foreground. Usually, when this happens, I don't photograph it but sometimes I find I have to make up for this lack of intresting elements myself with objects found nearby. So I move things. Once, for instance, I asked a car park attendant not to let cars park around a derelict merry-go-round. Without understanding the meaning of my request be was kind and allowed me to take the photograph I had in mind”.

The photographer does not conceal the fear that her use of the flash may in some way seem over theatrical, that it may “make certain things tee spectacular”. But she is well aware that, when balancing her general approach, this is a risk that she has to take.

These pictures by Raffaela Mariniello are based en a mixture of the natural and the artificial. The photographer is totally aware how inseparable these two elements are, especially when touching on the subject of the landscape.

Landscape is, indeed, a space where nature and culture blend continuously, producing ever-new forms.

Every place new, particularly in Italy, bears the mark of the contrivance of living, and by living - as suggested by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger - I mean all the manifestations ofhuman living.

We can say that nothing belongs entirely to nature, to wildness. This is something Giacomo Leopardi had already realized in the early 19th century when he wrote: "A huge part of what we call natural is not; indeed it is quite artificial.That is to say. the tilled fields, the trees and the other plants neatly arranged, the narrow river kept within certain confines and steered in a certain course, and the like, have neither the state nor the appearance that they would have naturally".

In actual fact, during his existence, man experiences wildness as a threat and thinks that only by taming it can be live. In this way, the history of mankind has become a constant removal of "wildness" from nature a never-ending working of the contrivance of living So that man has created his landscapes.

Raffaela Mariniello started from this realization to construct her Neapolitan portrait - one in which nature and contrivance live together, adopting the form of a living, pulsating reality.

“Yes - she says -, that is it, I see these photographs as portraits: of Naples and of the Neapolitan people, for better or worse”.

I ask her about the bane of Naples and she answers that it all lies in individualism. She tells me: "There is no collective awareness.

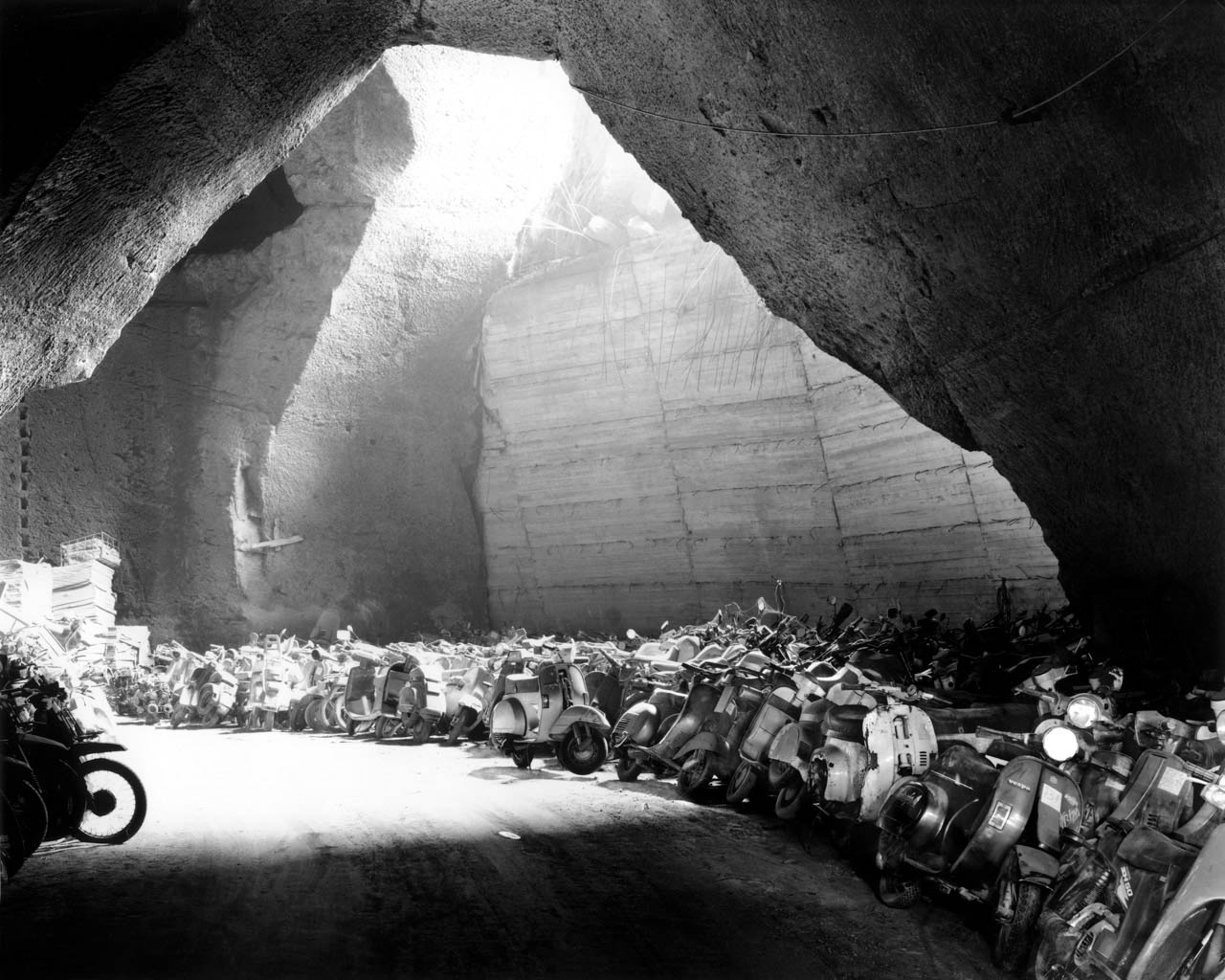

There is no common space. The people are practically obsessed with cleaning their own spaces and, as they clean, they throw everything out into what they consider no one's space. So, the degradation seems perfectly natural to the people. Even improvised dumping grounds are considered normal".

I point out that something similar also happens with peoples that are commonly thought to have greater civic responsibility: the world's (rich) north throws its rubbish to the (poor) south, thus implementing the same amoral individualism, only a few thousand kilometers from what it considers its own home.

"Yes, that is true, but I would like - she says - the Neapolitans to find the strength to have a greater sense of participation in the near future". Then, alter pausing, she adds: "Nevertheless, from a creative point of view, I find all this chaos stimulating. It stimulates my desire to put order".

Immediately and with a sense of relief, I think that this remark sharply contradicts a phrase that Theodor Adorno jotted down between 1946 and 1947 and that I have always found almost the quintessence of ideology: "The current task of art is to introduce chaos into order".

In actual fact, I believe that it is always exactly the opposite: that, in every period, the task of those who create has always been to produce order. Sometimes a new order, but always starting from a yearning for order.

Disorder like wildness - or, you could say, disorder as a form of wildness - is what most frightens man. Therefore he uses his great creative capacity to overcome it, to achieve what believes is a state of harmony, however fleeting.

"From that window you can see a charming distant landscape" in 1875, Pietro Fanfani and Giuseppe Rigutini used these words to illustrate the concept of landscape in their italian language dictionary. This illustration was extremely similar to that made By Daniello Bartoti in his L'uomo al punto (1655): "Through a window opening, and any other aperture you may fancy, show a glimpse of a distant landscape”

The word landscape has, thus, from the very first been linked to the concept of distance. Inescapably linked to this very concept is the famous definition by Rosario Assunto, the landscape philosopher par excellence "The space that forms to become landscape is one in which infinity and finiteness meet moving one into the other". Not all space can, therefore, be considered landscape Neither boundless space - such as the sky or the sea, which may of course also be the subject of an aesthetic experience - nor closed space (a courtyard or a square) can be considered landscape.

In order to be defined such, landscape must be a limited space opening in the distance, in which finiteness and infinity interpenetrate. In terms of figurative representation, I believe we should confirm the idea of Rosario Assunto, who magnificently defined landscape as a space that in its finiteness opens towards infinity and, en this basis, highlighted an extremely important fact "the city is not landscape, it relates to the landscape not in terms of function but of representation: as two geometric expanses relate to each other two meta-spatial places”.

A road or a square does not constitute a landscape, but they can be in the landscape, just as the landscape can be in them. Italy has wonderful examples of this - towns where the landscape enters the streets and the streets become a part of the landscape Suffice to quote the sensation experienced by Nietzsche in Turin: "...from the centre of the city you can see the snow-capped Alps! The streets seem to take us straight up there. The air is dry, sublimely pure".

As I have written elsewhere, it is therefore incorrect to speak of urban landscape; it is a sign of analytical confusion or, if you prefer, of a certain hasty compromise. When we use the expression "urban landscape" it ought to mean "landscape seen from the town" or "the town in the landscape" In the absence of these two specific conditions, when photographing in a city we ought to speak of urban views, or use the English definition townscape.

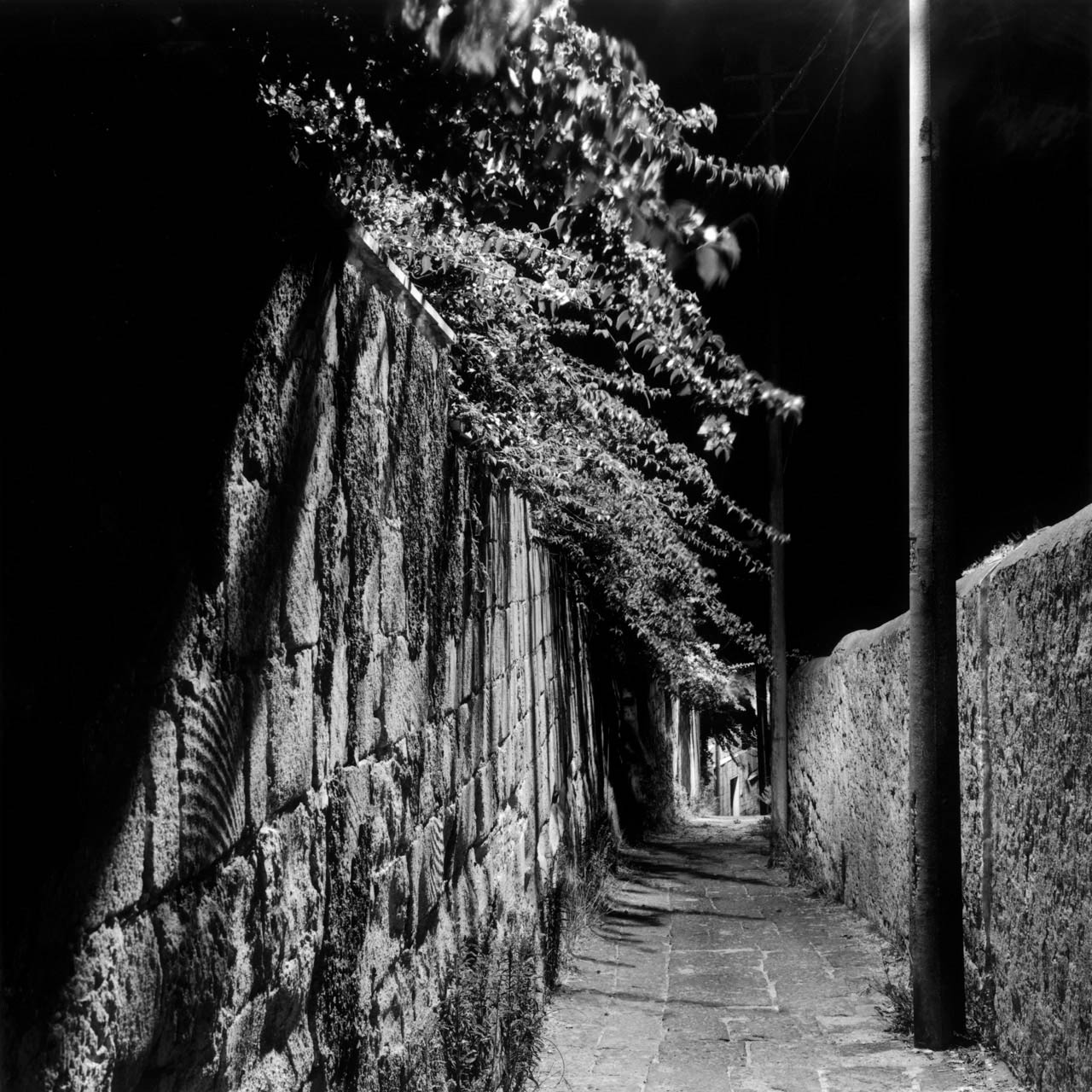

On the basis of this reasoning, when browsing through the photographs collected by Raffaela Mariniello in this book, basically we are faced with townscapes in which very frequently landscape and nature are truly present.

Indeed, the photographer herself stresses this fact. "Even in the city - she says -, I look for a view towards infinity. I am attracted by the sense of distance, the open. My photographs always have a foreground and a background. And there is always some reference to nature: a tree, a tuft of grass... When I am walking, I instinctively notice the natural, the sense of nature. You always have to start from the land, its manifestations. On closer examination, you realize that nature has an irrepressible force. It resurfaces constantly even in the city. Just look at sites that have been abandoned for a few years and you realize that trees have re-appeared and grass has grown. Yes, even in the city, I look for the natural, in the wind for instance." One thing stands out immediately as you look at these pictures by Raffaela Mariniello: the fact that they were taken at what is often the crucial moment in many fantasy stories, dusk. For many - even in these times of technological and rationalist certainties - this is still a slightly anxious time (as light disappears and the immensity of night falls, from the innermost depths even of modern man emerges a - conscious or unconscious - fear that the sun may never return).

This is Raffaela Mariniello's favourite hour, that when she took the photographs in this book: moving from the Vesuvian towns (San Giovanni, Portici, Ercolano, Torre del Greco, Torre Annunziata) to the Phlegrean Fields, to Pozzuoli, Baia, Cuma and Arco Felice, and with the sea-front and port of Naples as the main focus of attraction.

For her this is the crucial creative hour, when she can bring together the fading light of day, that of the street lamps and her flash. “I need artificial light- she says – and, with it, natural light”. This is why she goes out without a camera during the day, looking for places to capture at dusk. She conducts what we call reconaissance. Then, when, the afternoon draws to its close, she loads her photographic equipment into the car and, with a couple of friends who also act as assistants, goes to face the surprises of dusk, which in her case spring from the social degradation of the places visited. “I frequently photograph very down-and-out places and I often feel a great sense of unease - she says. There are nearly always huge rats and far from recommendable characters. I could never go alone; not only would I certainly be robbed of my equipment, but I would also run other risks. I always need the company of some friends. It is always very difficult to take photographs in this sort of reality and actually, en more than ore occasion, I have been unable to do so either for reasons of bureaucracy or criminal activity - in some cases both So. every time I manage to finish a job, I go home almost with a feeling of achievement."